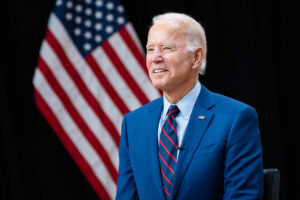

US-CHINA tensions have America’s closest allies in Asia strengthening their militaries. But in a boost to President Joseph R. Biden’s diplomatic efforts, that trend is extending to some Southeast Asian nations which have recently kept the US at arm’s length.

Philippines’ President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. is looking to buy Chinook helicopters and accelerate talks to implement a defense cooperation pact that would give the US military greater access in the country. The moves come six years after then-President Rodrigo Duterte ended joint patrols with American forces and sought more weapons from China.

Indonesia — the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation — has expanded joint exercises with the US, unveiled a $125 billion military modernization plan last year and is holding talks over the purchase of dozens of Boeing Co. F-15EX fighter jets. US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin praised the “significant advancements” in the relationship after meeting Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto last month.

Wary of being forced to pick sides between the US and China, Southeast Asian nations have historically struggled to find a middle ground. While many regional governments count on the US as a key security partner, China has been the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) biggest economic ally for 13 consecutive years, with two-way trade exceeding $500 billion this year.

President Xi Jinping’s more assertive foreign policy is shifting that equation for some countries as Beijing accelerates its military development and reiterates claims to Taiwan and a huge swath of the South China Sea. Regional governments have also been frustrated that efforts to negotiate a code of conduct between China and Asean in the South China Sea haven’t progressed.

“There’s a better appreciation that the US is an important factor of the strategic equation here and it’s in everybody’s interest that you stay around, and that’s a big change,” said Bilahari Kausikan, Singapore’s former permanent secretary for foreign affairs.

Mr. Biden will get a chance to make the US case to regional allies directly in his first trip as president to Southeast Asia this week, when he arrives to take part in an Asean summit in Cambodia and then heads to a meeting with Group of 20 leaders in Bali, Indonesia.

A State Department official said the US will work with regional leaders to ensure respect for international law and freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.

While Indonesia has long had a foreign policy centered around non-alignment, an ongoing territorial dispute with China around the Natuna Islands prompted President Joko Widodo to send warships to the area on multiple occasions in recent years.

‘IRONCLAD ALLIES’

Further incursions in waters claimed by the Philippines saw Marcos’ government lodge hundreds of diplomatic protests against Beijing less than three months into his term. That comes after the country boosted its defense budget almost 60% from 2017-2022, the most in Asia.

Mr. Biden called the US military alliance with the Philippines “ironclad” in a meeting with Mr. Marcos last year, a sharp shift from the Duterte era when some analysts feared the two nations’ mutual defense treaty could get scrapped in what would have been a huge win for Beijing.

“While we strive to live in peace with others, it is still crucial that our Armed Forces be modernized so that it is ready for all eventualities,” Mr. Marcos said Tuesday. The Philippines gets about $40 million in US security assistance annually, a State Department spokesman said.

US-China tensions and the threat from Beijing aren’t the only reasons regional governments are upgrading their defenses, but they “are clearly a driver of their procurement programs,” said Ian Storey, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute who specializes in regional security issues.

Overall, defense spending in the Asia-Pacific region now accounts for nearly a quarter of global investment, with China making up 46% of this year’s total, data from defense specialist Janes shows. Japan, South Korea, India, Taiwan and Australia are all forecast to expand spending significantly in the coming years, adding $100 billion to the region’s annual total by 2032.

Those spending plans could change quickly, given the need of governments to respond to inflation, tight energy supplies and expectations of a global recession. And to be sure, no nation is abandoning China. As they’ve done for decades, ASEAN governments are hedging their bets.

“The Biden administration is making all the right moves, but I am also somewhat skeptical,” said Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington. For instance, the US looks at Indonesia “as if they should be this natural partner and yet they’re very critical of US freedom of navigation operations,” he said, referring to the US practice of sending warships through the Taiwan Strait.

Officials in Beijing have pushed back on the US outreach, slamming what they call a “Cold War” mindset in Washington. And China has pushed an alternative to the US’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, trying to assuage regional suspicions of its intentions by emphasizing shared economic benefits.

‘BLOODY NOSE’

Bonnie Glaser, director of the Asia Program at the German Marshall Fund, said the developments in the region — but the Philippines especially — are likely getting attention in Beijing even if China isn’t reacting much publicly.

“My guess is that they note the trend and will privately suggest to some interlocutors in Southeast Asia that it isn’t in their interests to align themselves too closely with the US,” Glaser said.

The affinity in ASEAN for US weaponry or joint exercises doesn’t mean those countries would back Washington in a conflict, let alone take part in one. Frustrated by their own continuing disputes with a strengthening China, they mostly want a stronger deterrent so they can’t be totally dominated, said Storey of the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

If push comes to shove, “at least they could give China a bloody nose,” he said.

The Taiwan crisis has complicated matters further. US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taipei in August was seen in some ASEAN capitals as a step too far, unnecessarily provoking China. Beijing responded to the visit by unleashing its biggest military drills ever around the island.

In a sign of the region’s concerns, Singapore Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan warned last week that the geopolitical situation has become so bad that “the stage is almost pre-set” for a miscalculation or accident, akin to the events precipitating World War I.

That would be “a huge setback for both the US and China and the world, and especially for us in Southeast Asia, already grappling with the headwinds of the economic downturn, inflation, stagflation and still recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic,” he added. — Bloomberg